What Is This Big Yellow and Purple Moth?

Most of us follow some sort of routine after sunset or before retiring for the evening. First, I bring the bird feeder indoors. If I don’t, the raccoons will surely empty it—every last seed. Once, a few years ago, they had removed the feeder from the hook and entirely disassembled it.

Second, I turn on the front porch light, and, later, secure the storm door. If I hadn’t done this a couple of nights ago, I would have missed this visitor. In the few seconds it took to grab the camera, the moth had already slid partway down the glass. I’ve never seen one of these Imperial moths, and it was an impressive sight!

After taking photographs, I gently nudged the moth into a glass bowl for the night. She didn’t seem terribly eager to fly away, and didn’t require much encouragement. The plan included show-and-tell with a couple of neighbors the next morning before releasing the moth to the trees down the block.

This Imperial Moth Is a Big One

This Imperial moth has a wingspan of 5.5″, although adults normally measure from 3″ to 7″ wide. This one is a female. Males have more purplish-brown spotting on their wings. Another distinction involves the antennae on males, which are feathered in order to more easily detect pheromones given off by females.

In formal circles, she is known as Eacles imperialis imperialis (Drury, 1773). The Imperial moth is found in rural and suburban habitats from Argentina north to New England, and, in the United States, from the Rocky Mountains east to the Atlantic Ocean.

In the northern U.S. and Canada, its populations have been in decline since the mid 1900’s due to artificial lighting, pesticides, and diminishing habitat. This moth is quite common throughout the mid Atlantic region.

Life Cycle of the Imperial Moth: 4 Stages

1. The Egg

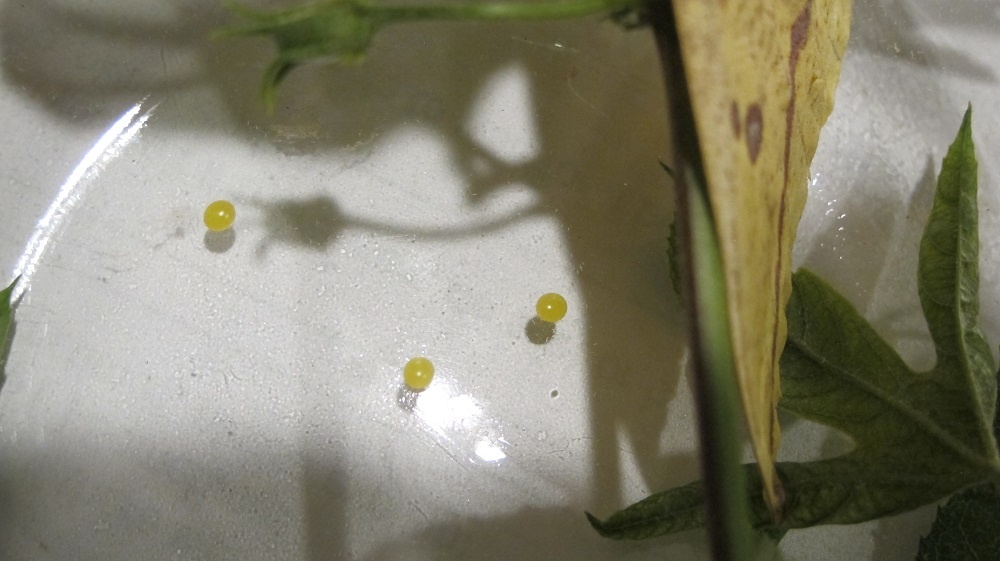

A small caterpillar emerges from the yellow egg in 10 to 14 days, consuming its shell (chorion). But the young caterpillars might roam for a few days, I’ve read, before settling down on the branch of choice. (***Update***: Eggs can hatch within a day or two, as documented under “They Hatched!”, below.)

2. The Five Instars

When it emerges from the shell, the larva can puff itself up to about 1/3″ long, appearing larger. The black spines (scoli) at the head and the posterior end might ward off predators.

After feeding for a while, the larva is ready to molt. The caterpillar attaches silk to the main vein of the leaf, and grasps the silk with its legs and prolegs. Each time the caterpillar molts, it expands, and the exoskeleton firms up. Sometimes the larvae eat their exoskeletons for the protein content.

As members of the Saturniidae family (the giant silkworms), Imperial moth larvae undergo 5 instars. During the first instar, the larvae are orange with black crossbands, and have short hairs. They grow darker after each molt, although there are regional variations and subspecies.

By the last instar, the caterpillars are 3.5″ to 5″ long. Color morphs will be dark brown, burgundy, or green, and they have long hairs and shorter spines. In sensitive people, these hairs and bristles can cause a rash.

The dark colored larvae have white spiracle patches, while green caterpillars have yellow spiracle patches. Spiracles are breathing pores, located in a line down each side of the caterpillar.

The University of Florida has excellent photographs at their website.

Food Sources

Larvae of the Imperial moth feed on native oak, maple, sweet gum, sassafras, and pine trees. Some websites indicate the caterpillars’ preference for pine trees. They also feed on eucalyptus, box elder, and Norway spruce. Less commonly, the larvae feed on elm, hickory, persimmon, honey locust, and many others.

This caterpillar is a favorite food source for birds.

3. The Pupa

After the 5th instar has matured, it burrows into the ground to pupate. The Imperial moth does not make a cocoon, as other silk moths do. The overwintering pupa is dark reddish brown to black, and has appendages on the posterior end that help it rise in the soil just before the adult emerges. While buried, it is not vulnerable to birds, although burrowing animals might eat it.

4. The Adult Moth

Adults emerge, usually at dawn, to mate. In the northern part of their range, adults appear in mid-summer (June-August). In the southern part of their range, they emerge over a longer period of time, from April through October.

Imperial moths have only one brood per year. In warm areas where they’re found, some observers have stated that they have 2 broods. But it is believed that the one brood is actually emerging over a prolonged period of time.

Males appear before the females. After mating, female Imperial moths lay eggs on foliage at dusk.

A Mommy Moth!

This is the ventral surface of the moth, and what I saw first. “Oh, wow!”

It appeared that the right hindwing had been damaged. So, I didn’t think she had recently emerged from her pupa. Imperial moths live only a week or two, for the sole purpose of mating and laying eggs. Their mouth parts have been reduced, preventing them from feeding. Neither the male nor the female takes sustenance as an adult.

To make the Imperial moth more comfortable during her overnight accommodations, I added some greenery from the garden. No, not for the purpose of providing food. I just thought she would feel more at home, while being held captive, until she could return to her natural habitat. Incidentally, people also benefit, psychologically, when we’re in the presence of living plants.

There was a surprise the next morning. A dozen eggs had fallen under the greens to the bottom of the bowl. So, dutiful subject that I am, I will place them on the leaves of an appropriate tree.

What fun! (Behemoth or Beshemoth?)

(***Update***: Over the past week or so, I’ve noticed a few more Imperial moths flying through the yard. Two of them were eagerly followed by hungry birds, but I didn’t see the birds catch them. 8/3/2020).

They Hatched!

By yesterday morning (7/25), about 2/3 of the dozen eggs had hatched. That was unexpected! So, I took a few leaves from the red maple tree (Acer rubrum) by the mailbox and placed them in the bowl. This morning, it was clear that they had begun eating. The edges of the leaves were nibbled (photo, right), and tiny dark feces fell to the bottom.

By yesterday morning (7/25), about 2/3 of the dozen eggs had hatched. That was unexpected! So, I took a few leaves from the red maple tree (Acer rubrum) by the mailbox and placed them in the bowl. This morning, it was clear that they had begun eating. The edges of the leaves were nibbled (photo, right), and tiny dark feces fell to the bottom.

(***Update***: When I read that Imperial moths can be raised in captivity, I decided to keep the eggs. I assume that Mommy Moth laid the rest of her clutch after I’d released her. 8/4/2020)

The remaining eggs hatched last night, and those caterpillars were visibly smaller, but only slightly so, than their older siblings. I brought them to the kitchen table to photograph them. If they weren’t eating (the maple leaf, that is), they headed toward the brightly lit patio door, requiring persistent redirection. This reminded me of sea turtle hatchlings scurrying instinctively toward the water.

First Silk For the Imperial Moth

I gathered all but a few of the caterpillars, placing them and a maple leaf in a bag for release. At the maple tree, I placed each one on a leaf, until it “stuck”.

Newly hatched larvae attach themselves to the leaf with a fine silk thread, apparently not just during molting. When I picked up the tiny caterpillars to place them on the leaves, I could feel the resistance of an invisible thread. Smart little caterpillars.

White Hairs

Something else I noticed concerned those hairs on the caterpillar. All caterpillars had the black scoli and many white hairs. Most of those hairs seemed to be somewhat irregularly placed on the caterpillar, although others were extensions of the scoli. And, coincidentally, the maple leaves had fine white trichomes (extensions of the epidermis) on the back of the leaf, mostly along the main veins. The trichomes and many of the hairs on the larvae looked exactly alike.

It looked as though they might have picked up some of those trichomes, because some caterpillars had several hairs around their heads, and others had very few. Most hairs on the segments appeared to have been randomly placed and at odd angles to each other.

- One day old. Ruler marks are 1/16″ apart.

- Two days old.

***Update***: The following section was added 9/14/2020.

New Food For the Imperial Moth

For a few days, I added different types of leaves to see if the caterpillars demonstrated a preference. They were not interested in loropetalum, oak, holly, or passiflora. They did, however, love the crape myrtle—more than they liked the native maple. When offered a buffet of several kinds of freshly picked leaves, including maple, the caterpillars ate only the crape myrtle. How perplexing that the caterpillars preferred this non-native tree (Lagerstroemia indica)! And, surprisingly, they lost all their white hairs (photo, above) after feeding on crape myrtle for a few days.

To attract more wildlife to your property, plant a large number of native plants. As we’ve seen with this imperial moth, our native insects and birds will feed on some non-natives as well. But the best bet is to plant more natives than exotic species of plants. Choose plants that flower at various times of the year to attract more species of insects and animals. And plant them in multiples; a single specimen plant might not get the attention from a female insect looking for a nursery to host her young. Contact your local native plant society for plant species recommendations.

Keep in mind that lawn chemicals and insecticides could kill imperial moths while they’re pupating in the ground.

I released the caterpillars to a 6′ crape myrtle. This plant had volunteered in the front garden from seed and was transplanted into a 5-gallon pot. The larvae regrew those fine white hairs and now all caterpillars are thriving in their new home!