Mabry Mill

Last month, a leisurely drive took me to Mabry Mill in Meadows of Dan, Virginia. It was an easy detour from a few of those towns in northern North Carolina I had been exploring. During this pandemic, with social distancing in mind, day trips are pleasant diversions. My mother and I called them “mental health drives”.

I’ve spent the past few months looking for property with more sun, more space, and no homeowners’ association. The goal: large gardens for pollinators, butterflies, and birds. Raise greens and vegetables, and maybe a dog. Fix it up while working part-time? Open a little plant shop? The possibilities are exciting! With the vaccine apparently a likelihood, maybe more properties will soon come to the market.

For years, the western part of North Carolina was the location of choice. But, for the past month or so, I’ve widened the search to include counties in the northern part of the state. Lovely area, beautiful terrain, home to several vineyards. This is where people waved from their riding mowers as I drove by.

Getting to Mabry Mill

The mill is located at milepost 176.1 (watch for signs) on the Blue Ridge Parkway and is administered by the National Park Service. This is a truly memorable drive and part of the National Scenic Byways system. The Blue Ridge Parkway winds 469 miles through the southern Appalachian Mountains. Elevations range from 649′ near the James River, Virginia, up to 6053′ on the slope of Richland Balsam Mountain (milepost 431) in North Carolina.

The Parkway connects the eastern side of Great Smoky Mountains National Park, which straddles the border between Tennessee and North Carolina, and Shenandoah National Park in Virginia. It continues northward as Skyline Drive, from where it intersects with U.S. Interstate 64 near Afton VA, to Front Royal VA. The Blue Ridge Mountains are part of the larger Appalachian Mountain chain.

But don’t expect to whiz by at interstate speeds; this is a slower road, with over 380 stopping points. There are many intersections along the faster U.S. or state highways where you can pick up a local stretch of the Blue Ridge Parkway. And gas up the car before reaching the Parkway because there are no filling stations on this road.

Caution

Keep in mind that people live and work here, so there might be farm vehicles on or crossing the Parkway. And check with the National Park Service to see if hazardous conditions or inclement weather might have closed parts of the Parkway.

Camera’s Ready

Very picturesque. The entire area presents scenes of astonishing beauty, with views of pastoral landscapes, deep valleys, and mountain vistas. If you need to get away from it all, come to the Blue Ridge Parkway.

The “blue” in Blue Ridge derives from the Cherokee Indian description for the mountains, an area they and their ancestors have inhabited for over 10,000 years. Their term translates to “land of blue mist”. Isoprene compounds (hydrocarbons) are released from and protect the trees in hot sun, cloaking the distant hills in a bluish haze. The Mohawk, Iroquois, and Shawnee also inhabited this mountain chain, with the Cherokee centered around the Great Smoky Mountains at the southern terminus of the Blue Ridge Parkway.

This was my second visit to Mabry Mill, and I had a particular goal in mind: pictures of fall foliage! Although there was some color in the trees and shrubs, the bright reds and oranges of sourwood and maple, and the glowing gold of hickory, had already passed. A gentleman in the restaurant informed me that, just a few days prior to my visit, a wicked wind had stripped much of the fall color from the trees.

Photographers after the perfect shot of the mill and its reflection waited for the pond water to stop rippling after a young boy had stirred it up. But no one complained. He was having a great time! A few of us exchanged “Oh well” glances, and made sure we were positioned to capture the moment.

Building Mabry Mill

Edwin B. Mabry and his wife, Mintoria Elizabeth (“Lizzie”), had acquired the property and water rights around 1905, and finished construction of the gristmill three years later. By 1914, the gristmill, the sawmill, and blacksmith and woodworking shops were providing services for residents living in the area. A sorghum evaporator and the remains of the whiskey still also can be seen.

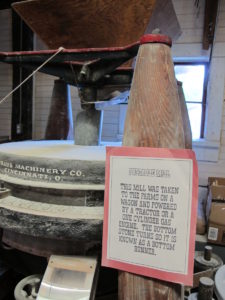

Mabry built a system of concrete tributaries, which collected water from streams above the mill, and directed it toward the wooden flumes (photo, right). Those flumes, in turn, channeled water toward the race, which fed water to the overshot waterwheel.

Because the water flowed slowly, the gristmill (called a “slow grinder”) ground corn with less friction, preventing the grain from overheating and burning. This earned the Mabrys a reputation in the region for producing products of excellent quality.

A few years after the mill and the shops were operating, around 1918, the Mabrys built their new home. It has since been replaced with a wooden structure once owned by the Marshall family (photo, below). The house on the site was built in 1869 near Galax, and donated to the National Park Service in 1956.

The old Marshall house.

The National Park Service

The Parkway’s construction began in 1935 at Cumberland Knob, milepost 218, just south of the border between North Carolina and Virginia. In 1938, two years after Ed Mabry died, the National Park Service purchased Mabry Mill.

Restoration of the historically significant mill and other buildings was completed in 1942. By then, gristmills had been rendered obsolete by more efficient large-scale milling operations and transportation networks that shipped products throughout the country.

The site is home to the restored mill, the wooden residence, and the workshops. This property includes short walking trails, a restaurant, and a gift shop, where you can pick up publications and maps. The restaurant closes for the season in early November, so check first if you’re hungering for their famous pancakes.

On certain days through the year, the National Park Service conducts craft demonstrations recounting ways of the past. They also bring in live musical performances to entertain visitors. The day I was there, Park Rangers Chris and Tabitha welcomed questions and shared information about how residents met the many challenges presented to them at that time. Each year, hundreds of thousands of travelers from around the world stop at the mill.

- Park Ranger Tabitha explained different uses for various kinds of baskets.

- Park Ranger Chris demonstrated dying wool, using pokeberry, indigo, jewel weed, and goldenrod.

Seeing how others lived just 100 years ago gives me renewed appreciation for our more modern conveniences. Now that my mother has passed, I enthusiastically look forward to life in a more rural location…one with those modern conveniences.

Farther Up the Road

In no rush to get home, I drove for another two hours or so, northward on the Blue Ridge Parkway. There was so much to see; each stop had its own unique view or plant life or structure to learn about. Trail’s Cabin, Shortt’s Knob Overlook, Rocky Knob, Rakes’ Mill Pond…and that’s only one small segment. Informative signs provide more details at the various sites.

“There’s something for everyone” along the Blue Ridge Parkway. If you’re curious about the history of a region or its natural wonders, if you enjoy photography or painting, bicycling or walking the trails, it’s all here. Check before you go to see when campgrounds, visitor centers, and picnic locations will be open.

Within a few miles of the Parkway are hundreds of attractions, including museums, folk art centers, performance theaters, lodging, restaurants, water sports, caverns, and fishing opportunities. Enjoy the friendly vibe or the local craftwork in any of the quaint shopping districts not far from the Parkway.

Biodiversity

The Parkway accommodates tremendous biodiversity. According to one pamphlet, 159 kinds of birds nest along the Blue Ridge Parkway, and dozens more migrate through it. 130 species of trees, 1600 kinds of plants, and 74 kinds of mammals (including bears) live here. Near one of the gorges, a sign indicates that 25 species of native ferns inhabit that area.

The Parkway accommodates tremendous biodiversity. According to one pamphlet, 159 kinds of birds nest along the Blue Ridge Parkway, and dozens more migrate through it. 130 species of trees, 1600 kinds of plants, and 74 kinds of mammals (including bears) live here. Near one of the gorges, a sign indicates that 25 species of native ferns inhabit that area.

More than 50 species of threatened or endangered plants occupy terrain around the Parkway, so tread respectfully.

Among the oldest land formations on earth, the Appalachians got their start 1.1 billion years ago. From that time up to around 250 million years ago, European and North American tectonic plates collided, pushing up this mountain range that stretches from Pennsylvania to Georgia.

The Appalachians once were as high as the Rocky Mountains, but erosion slowly reduced their elevation. Now, the tallest mountain east of the Mississippi River is Mount Mitchell, reaching 6684′, near milepost 350, west of Old Fort NC. These cooler mountain tops support evergreen spruce-fir ecosystems, also found in the northern United States and Canada, while mixed hardwood forests occupy the lower elevations.

As rivers and streams shaped the surface of the land, pockets of territory became isolated from each other. Smaller “niche” ecosystems evolved, each with its own assortment of organisms. Geographic isolation and a great deal of time are the primary drivers behind speciation. One kind of salamander might inhabit a particular streamside location, but not occur anywhere else in the world, not even over the next ridge.

From the first superintendent of the Blue Ridge Parkway, Stanley Abbott:

“A parkway like Blue Ridge has but one reason for existence, which is to please by revealing the charm and interest of the native American countryside.”

Modern living continues to extract more land for housing, transportation, and commerce. But, with conservation of natural habitats, the National Park Service has protected vulnerable ecosystems for wildlife and preserved the history and character of the region for all to see.

- Near Shortt’s Knob Overlook.

- Woolly bear caterpillar–larva of Isabella tiger moth. No, it cannot predict winter weather.

- Fall blooming native aster (Curtis’ aster, A. curtisii–?).

- One of several lichen species on these ancient rocks.

If you’d like to read another article about gristmills, this one at The Farm In My Yard describes one that is still working in North Carolina, and dates from pre-Revolutionary War days: The Old Mill of Guilford. (Try their gingerbread mix!)

2020: The Year That Wasn’t?

Well, it’s almost over. We have the holidays to look forward to, right? Oh wait; here, we can’t gather indoors in groups numbering more than 10… Some areas are discouraging any kind of indoor celebration. I wonder what most American families will do.

There will be turkey roasting in the oven while freshly baked pumpkin pies cool on the counter. We’ll celebrate Thanksgiving (400th year since the Mayflower) and Christmas, although new traditions—new ways of gathering—might be born. (With respect due the native Indian cultures, I acknowledge that not everyone celebrates this day.)

How will your holidays look different this year?

Such misery this pandemic has caused many millions of us: jobs lost, loved ones lost, businesses closed, weddings postponed, school children missing out. The good news on the radio this morning announced another pharmaceutical company that has developed a vaccine for the virus. If it’s safe and effective, sign me up.

If all we can do is gather outdoors, then so it shall be. No problem; I’ll gather the camera and some snacks, and be off to some not-too-distant location…somewhere in nature, which, for me, never fails to rejuvenate.

This has been a difficult year for all of us, all around the globe. Good days are on the horizon, though, and I wish you happiness and good health. There’s still so much to be grateful for. Let’s celebrate that.

A paved pathway takes visitors through a succession of gardens. There’s an herb garden, a fragrance garden, and one that highlights tropicals. And a miniature train garden, succulents, and roses. Annuals are planted here and there, providing vibrant color and nectar for the

A paved pathway takes visitors through a succession of gardens. There’s an herb garden, a fragrance garden, and one that highlights tropicals. And a miniature train garden, succulents, and roses. Annuals are planted here and there, providing vibrant color and nectar for the