Can we grow new potatoes from old potatoes?

Yes!

So… those potatoes left in the pantry or the bottom of the refrigerator decided to sprout. Instead of throwing them into the trash or the compost bin, try growing them! You can grow potatoes in the home garden or in large pots, following a few simple guidelines.

Too withered for consumption, but fine for the garden.

We don’t recommend planting potatoes recently purchased from the grocery store because they’ve likely been treated with a sprout inhibitor. After the effect wears off, you’ll see the eyes begin growing. That, though, could take months.

Organic potatoes, if treated with sprout suppressors approved by the National Organic Program, sprout earlier than non-organic potatoes. Inhibitors, such as spearmint, peppermint, and clove oils, must be applied more frequently than chemicals used on traditionally treated potatoes.

Spouting potatoes (like the ‘Yukon Gold’ in photo, top) are still edible, after removing the eyes. Discard moldy and rotting potatoes. But save for the garden the ones with well-developed sprouts and those that have withered beyond the point of palatability.

Carbohydrates stored in the tuber provide energy for the developing shoots. When green leaves begin growing, photosynthesis will sustain the plant.

When can we grow potatoes outside?

Potatoes can tolerate cool soil, but not cold, wet soil or freezing temperatures. I live in USDA plant hardiness zone 7, where we plant early maturing varieties 4-6 weeks before the last spring frost. Gardeners plant mid-season and late varieties after that.

Wait for the soil to warm up to at least 45°F before planting tubers. Long-range weather forecasts might indicate whether it’s safe to plant or prudent to delay.

A garden exposed to full direct sunlight warms up earlier in spring than one in partial sun. Grow potatoes in full sun, but avoid exposing them to searing summer heat. Gardeners living in higher elevations or in cooler summer regions can grow potatoes through the season.

If the weather forecast predicts temperatures below freezing, I’ll mulch the soil with several inches of oak leaves, never in short supply around here. A thick, airy mulch insulates the ground from a sudden drop in temperature. Plants benefit from mulch kept in place all season. Not only does it moderate temperature, suppress weeds, and keep moisture in the ground, but it also prevents disease spores from splashing onto the potato’s leaves. This is easier to do in small garden plots than in larger farming operations.

Emerging foliage can tolerate light frost. It could take a few weeks for growth to show above ground.

Seed Potatoes

For a wider selection of varieties offered to farmers and home gardeners, look for “seed potatoes”. Some garden centers and many seed suppliers stock seed potatoes. They’re not actually seeds, but certified young potatoes almost ready for planting. Although they’re certified disease-free when purchased, plants are susceptible to a few pathogens as they grow.

Favorable conditions and good management practices decrease the likelihood of problems. If you’ve had diseases in your potato crops, don’t save potatoes year to year, but purchase certified potatoes instead. Don’t grow potatoes where they’ve been planted any time in the past 4 years.

Botanically speaking, potatoes are classified as Solanum tuberosum. They belong to the Solanaceae family and call tomatoes, peppers, and eggplants their cousins. Tobacco, petunias, and deadly nightshade, a poisonous weed, also belong to the nightshade family.

Potatoes are native to the cool mountainous regions of South America. In the 1530’s, European explorers gathered them and introduced potatoes to their homeland. Irish immigrants brought them to North America in the early 1700’s. Approximately 4,000 varieties of potatoes have been bred. True seeds, as opposed to seed potatoes, are poisonous when eaten and are used only for breeding purposes.

You can find potatoes with white, yellow, tan, red, blue, and purple skins and flesh. Thin-skinned potatoes, such as ‘Yukon Gold’, ‘Kennebec’, and ‘Red Pontiac’, grow well in the eastern parts of the U.S. The western states suit the thicker-skinned ‘Russet’ and other baking potatoes.

Crop Rotation

One of those good management practices involves rotating our crops. Related plants tend to be susceptible to the same pathogens and insect pests. When growing one crop in the same plot of land year after year, disease spores and insects can build up in that location. That’s why it’s recommended to move all members of a particular plant family to different plots over the next several growing seasons.

For example, if you grew potatoes, tomatoes, peppers, or eggplants in Plot A in any of the last 4 years, move your potatoes and other members of the Solanaceae family to Plot B this year, Plot C next year, and then Plot D the year after that.

Rotate among the various plant families, such as:

- brassicas—arugula, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, cauliflower, kale, etc., in the Brassicaceae family

- cucurbits—cucumber, squash, zucchini, melons, in the Cucurbitaceae family

- legumes—peas, beans, in the Fabaceae family

- lettuces, in the Asteraceae family

- onions, leeks, garlic, in the Amaryllidaceae family

- Swiss chard, spinach, beets, in the Amaranthaceae family

Several varieties of potatoes.

How To Grow Potatoes In the Garden

Step 1: The First Cut

Before planting potatoes in the ground, cut them into pieces about 1½” long. Each piece should have 2-3 eyes. Let them sit in the open air for 1-2 days to seal the cut surface. This helps prevent rot in moist soil.

Small potatoes can be planted whole.

Step 2: Prepare the Soil If You Want To Grow Potatoes

Thorough soil preparation serves the immediate purpose as well as plantings in years to come. After improving the soil with generous amounts of drainage materials, you’ll need to add nutrient-rich amendments a few times each year after that.

Not repeatedly disturbing the soil profile retains healthy populations of beneficial microbes. Farmers are increasingly using no-till methods and cover crops to preserve soil structure and prevent erosion of valuable topsoil. Frequent tilling also introduces high levels of oxygen between the particles of soil, so organic matter is broken down too quickly.

Vegetable plants need good drainage, and potatoes are no exception. Loosen the soil at least 12″ deep, breaking up the clods. Potatoes struggle in compacted clay and stony soils; tubers that do form are often misshapen. Potatoes grow very well in raised beds.

Incorporate a few inches of pine fines, soil conditioner, peat moss, and/or coarse sand to improve the tilth (or workability) of the soil. Avoid layering materials in the soil profile. Layers of coarse and fine materials, with differing air pore spaces from one material to another, obstruct water percolating through the soil. This could cause soggy layers that can rot roots. For that reason, I never place a layer of gravel under plantings.

In the top 5″ of loosened soil, mix in compost, leaf mold, or planting mixes. These materials contain a variety of nutrients required by vegetables, and they encourage rapid rooting.

Aged manure and mushroom compost are not recommended for root vegetables.

Soil PH

Potatoes love heavily composted soil. They also require acidic soil, with a pH between 5.0 and 6.0. (Various websites recommend a pH anywhere between 4.8 and 7.0.)

Low pH helps prevent scab, a disfiguring disease of potato skins. Soil pH outside the preferred range for potatoes limits nutrient absorption and might cause nutrient toxicities.

Contact your local agricultural extension agents for information on taking a soil test. They can recommend preferred fertilizers, methods to lower soil pH, and varieties appropriate for your area.

Step 3: Place the Seed Potatoes

In rich, organic soil, simply lay the potato pieces on top of moist, loosened soil or nestle them into the surface. The eyes should face upward. Then mulch over the seed potatoes.

They’ll also grow when planted 2″ deep. Space potatoes 6-12″ apart, depending on variety. Because potato plants grow 2-3′ tall and might sprawl a bit, allow 30-36″ between rows.

Mulch the bed with a few inches of leaf litter, shredded leaves, and pine needles to cover the planted potatoes. It’s important to adequately shade the surface of the ground from sunlight to protect growing tubers from greening…

“Greening”?

Potatoes with green skin needed deeper mulch.

Greening is caused by exposure to light, which, in itself, is not harmful. But the green pigment (chlorophyll) in potatoes is associated with the formation of a toxic glycoalkaloid called solanine.

Never eat green potatoes; if only the skin is green, cut off and discard that part before cooking. Never eat leaves, stems, or the berries that develop on potato plants.

Solanine in potatoes is more concentrated when growing potatoes in high nitrogen soils and in soil that’s compacted or very sandy. Bruised potatoes, those held a long time in storage, and potatoes with large eyes are higher in this toxin. The greener the potato, the higher the level of solanine. This bitter substance is a natural repellent to insects and browsing animals.

Solanine can’t be boiled or cooked away. The level is somewhat lower in foods fried at very high temperatures, but that brings its own problems, described later in this article. I’m not intent on discouraging you from growing or eating potatoes, but moderate consumption of this popular vegetable and proper preparation make it a healthier indulgence.

Symptoms of solanine toxicity include vomiting, diarrhea, slow pulse or breathing, low blood pressure, and abdominal pain. It can cause coma and death in rare instances, so be very careful with green potatoes. If any of the flesh is green after removing the skin, I would discard the potato.

Step 4: Maintenance

Water

Water the garden thoroughly after planting and mulching. If rain is unreliable, water the garden every week, never letting the soil become dry. Provide 1-1½” of water each week if it doesn’t rain.

Avoid wetting the foliage, and water in the morning so the foliage is dry going into the night. This helps cut down on the incidence of disease. Some varieties are resistant to blight, scab, Rhizoctonia, and Verticillium wilt. Those that have not been bred with disease resistance often produce great yields when using good gardening practices.

Hollow Heart and Brown Center

Some large varieties, particularly ‘Atlantic’ (for potato chips) and ‘Yukon Gold’ (a personal favorite), might show hollow heart and/or brown center. These are physiological disorders characterized by a star-shaped cavity and a central area with dead brown tissue, respectively, in the center of the potato or near the ends.

These stress-related conditions often result from inconsistent soil moisture—for example, wet soil after a period of dry soil. In addition, a period of prolonged cold weather during tuber formation can cause brown center. Spacing seed potatoes too far apart and using small seed potatoes (with too few eyes) can be the cause. Low potassium and other nutrient deficiencies can initiate the disorders.

The potato’s skin shows no indication of a problem. Affected potatoes aren’t perfect but are still edible.

Hilling Up

As the plants grow, hill up soil against the stems of the plants. Take soil from another part of the garden, adding a few inches up the stem and about 12″ out from it. This is an option—not necessary—but it should increase the yield.

Like tomatoes, potatoes root along buried stems. As they root, they’ll develop another layer of young potatoes at the ends of the stolons. Hill up around the stems 2 or 3 times during the growing season to maximize the harvest.

An alternative is to start potatoes in a moderately deep trench, reserving excavated soil on the side of the bed. Periodically fill in the trench with amended soil, a few inches at a time.

Fertilizer

Every few weeks, apply a complete fertilizer. The 3 numbers on the package representing nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium (N-P-K) should be in a ratio of 1:1:1 or 1:2:2. Avoid fertilizers high in nitrogen. An analysis close to 10-10-10 or 5-10-10 is adequate.

Although you could use chemical fertilizers, they tend to damage populations of beneficial microbes. But, until the soil warms up, microbes aren’t sufficiently active to break down the organic components into molecules the plants can absorb. That’s when I use chemical fertilizers, and then switch to organic products when the soil warms.

To help prevent disorders in developing potatoes, it’s recommended to apply smaller concentrations of fertilizer more frequently.

Insect Pests

Colorado potato beetles can be especially bothersome as they consume significant amounts of foliage. Inspect the undersides of the leaves for yellow-orange egg masses and remove them. The beetles have 10 black stripes on their tan wings. Immature larvae are orangish-red with 2 rows of black dots down each side. Bacillus thuringiensis var. tenebrionis, a biological insecticide, kills this beetle.

Aphids might congregate in large numbers on the plants. A brisk spray of cool water from the hose takes care of most of them. Encourage ladybugs, braconid wasps, and green lacewings to populate your garden. For severe infestations, prepare a solution of horticultural oil and spray early in the morning. Apply the solution to the bottoms of the leaves as well. Read the label.

Cutworms feed on sprouts emerging from the ground. Since these C-shaped larvae become moths, treating the potatoes with Bacillus thuringiensis var. kurstaki effectively kills them. Keep in mind that they’ll have to eat some of the foliage in order to ingest the Bt.

Slugs and Deer

A slug.

Slugs reproduce rapidly in moist conditions and where they can hide in crevices during the daytime.

Lay a board on moist ground, and slugs and snails will gather there after feeding through the night. You might notice those silvery slime trails on tender foliage. Early in the morning, take an old knife to the garden and… dispatch them forthwith! Or use organic Sluggo or similar product, which does not contain toxic chemicals. Except to slugs and snails. Read the label.

Although potato foliage is not the favorite choice of warm-blooded animals, deer and others will feed on it when not much else is available.

Other members of the nightshade family also host these pests. Row cover secured over the planting excludes most insects and browsing animals.

Potatoes that sprouted in storage are now growing new plants in 6″ pots. They’ll need protection from hard frost if planted, but I didn’t want to delay planting the deteriorating tubers.

Headings

Page 1: Can we grow new potatoes from old potatoes? (When can we grow potatoes outside?, Seed Potatoes, Crop Rotation), How To Grow Potatoes In the Garden, Step 1: The First Cut, Step 2: Prepare the Soil If You Want To Grow Potatoes (Soil PH), Step 3: Place the Seed Potatoes (“Greening”?), Step 4: Maintenance (Water, Hollow Heart and Brown Center, Hilling Up, Fertilizer, Insect Pests, Slugs and Deer)

Page 2: Step 5: Harvesting!, How To Grow Potatoes In Containers, Grow Potatoes For Their Nutrients (The Power Of the Purples, Potato Skins, Resistant Starch), The Problem With High Heat

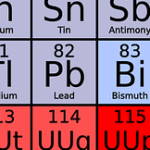

In 1977, the Consumer Product Safety Commission banned the use of lead paint in residential properties. If you live near an industrial region, a busy highway, or where lead paint might be a concern, I strongly advise testing for lead before you prepare the soil. Local zoning authorities should have records on past property use. For more information, contact the National Lead Information Center at 800 424-5323.

In 1977, the Consumer Product Safety Commission banned the use of lead paint in residential properties. If you live near an industrial region, a busy highway, or where lead paint might be a concern, I strongly advise testing for lead before you prepare the soil. Local zoning authorities should have records on past property use. For more information, contact the National Lead Information Center at 800 424-5323.