Miniature Lights for… Warmth?

Yes! You can use strings of miniature lights to prevent frost from damaging tender transplants in the garden.

This article originally was written for springtime applications. But read through, and you’ll see how the same principles work for cold weather gardening in many regions. These lights will keep greens in better condition, sometimes all the way through winter. Your cool season greens can produce for weeks or months beyond the early freezes!

Unpredictable

The weather has been so weird this spring. Some days it feels like June, and others skim the bird bath in ice. Lots of us already planted tender (easily damaged or killed by frost) vegetables and flowers. Without some protection, they will be injured by the cold nights that are still in our forecast.

If the nighttime temperatures are predicted to fall below 50°F, I’ll cover tomato and pepper transplants in the garden. A night or two in the 40’s probably won’t hurt most transplants if they’ve been properly hardened off. But consistently chilly weather will slowly rob the plants of their vigor. Peppers and basil are particularly sensitive to cold soil, and can be killed by it, even if temperatures aren’t close to freezing.

It’s amazing to see snow still flying in some of our northern states. It is beautiful…to watch on TV.

Early winter in the cold frame. Light strings snake around the bottoms of the pots.

Miniature Lights

Incandescent lights, as opposed to LED’s, give off gentle heat. Those 100-bulb strings of miniature incandescent Christmas lights can increase the temperature under cold frames. They also protect tender plants in garden beds when covered with plastic sheets to hold the warmth.

Potted plants under cover, warmed by miniature incandescent lights.

This is especially beneficial in those locations where an upside-down bushel basket will not sufficiently ward off the cold. And I’m not suggesting that you attempt to defy good garden sense by planting peppers in February in Minneapolis. There are limits!

When I calculated the wattages, square foot coverage, and costs, the miniature lights were the most economical option for my purposes. Each 100-bulb string provides warmth equivalent to a 40-watt incandescent bulb. I also considered heat mats and heat cables. Have a look around hardware stores and see what garden centers have available. Look for ideas online or with mail order companies selling farm, garden, horticultural, or greenhouse supplies.

Use “indoor/outdoor” products that are safe to use in humid environments. Space heaters designed for indoors are not good candidates outdoors. If you’re planning a project outside your comfort zone, check with licensed contractors, especially for electrical work.

(***Update***: Above average temperatures in the Carolinas carried into mid-fall, so the amaryllis bulbs refused to die down. Recent nighttime readings in the low to mid 20’s would have damaged the potted bulbs, so they’ve been enjoying temperatures in the mid 40’s, thanks to miniature lights and a plastic cover. Not forcing early dormancy on the plants gives them extra time to photosynthesize and, perhaps, an additional flower bud. Finally, the leaves are beginning to yellow, and soon they’ll come indoors to rest and to begin the bloom cycle. December, 2018)

And More Bright Ideas

Include snow loads and wind events (they will happen) in your plans. Slope the top of a cold frame away from the house to allow run-off. During the occasional heavy snowstorm in Maryland, I got up in the middle of the night to sweep off snow that had accumulated 8-12″. Toby, our second Rhodesian ridgeback, thought this was lots of fun. Although polycarbonate is very durable and will bend with weight, too much distortion will allow frigid air to enter and might collapse the frame.

There are more permanent alternatives to consider. Do-it-yourself greenhouse kits could be used specifically for fall and winter crops, heated or unheated. Familiarize yourself with local weather patterns to decide what’s feasible…or necessary. You might be able to convert a shed or construct a lean-to by adding a few materials readily available from the hardware store. Contact your local agricultural extension agent for practical suggestions or check out the numerous online videos.

Cold Frames With Miniature Lights

Setting up cold frame with new strings of miniature lights.

Cold frames are simple glazed structures that give extra protection to plants when the weather is unsuitable for planting out. Young seedlings or transplants can be hardened off here until they’re ready for the garden. Also, plants that normally go dormant or die in winter can be kept green in a frame. And edible cool season vegetables can grow all winter in a cold frame where it’s too cold out in the open.

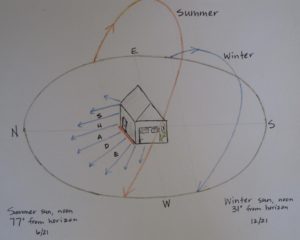

Try to orient the frame’s exposure toward the south (in the northern hemisphere), which will give the greatest benefit in terms of heat gain. Bricks on cinder blocks (photo, right) elevate the north edge of the glazing for rain run-off and a more favorable aspect to the sun.

Each hour of direct sunlight shining on the frame keeps the temperatures elevated and stores warmth in the ground. If possible, locate the cold frame out of the wind and in a warm microclimate on the south side of the house or shed.

Materials

Some gardeners use lengths of sturdy wire, arched and stuck in the ground, covered with clear plastic secured by fasteners. Or use long pieces of PVC tubing anchored over rebar sunk in the ground. Repurpose old storm windows or doors (without lead paint) propped on a support.

“Low tunnels” or “caterpillar tunnels” are available at garden centers or online, complete with supports and coverings.

For the large frame in Maryland (photos), I used rigid twinwall polycarbonate panels, covered with clear plastic film to close the sides. On very cold nights, I added more sheets of plastic, separated by “netted” plant flats that trapped air between the layers. This created dead air space and better insulation.

Cold frame in MD, vented in the daytime.

Houseplants

Oxalis, succulents, stellar geraniums, a variegated fig tree, and other houseplants (photo, top) survived the winter, although I did not expect them to grow. When cyclamen plants went out of bloom in the house, I moved them to the cold frame, where they happily set buds once again.

Plants that do not tolerate the slightest chill, such as African violet, Alocasia, pothos, philodendron, and basil, would not survive very long at temperatures below 60°F. They stayed indoors for the winter.

“Frame to Table”

Without using miniature lights in Maryland’s colder winters, I would not have been able to harvest this assortment of greens. I grew lettuces, leeks, arugula, hon tsai tai, mustard spinach, dinosaur and ‘Red Russian’ kales, and spinach. And Swiss chard, tatsoi, pac choi, mini broccoli ‘Happy Rich’ in wide, shallow pots, about 6″ deep (such as those in photo). ‘Nabechan’ bunching onions and some greens grew in the ground on one end of the cold frame, while potted crops sat on the brick surface.

Greens growing in wide bowls.

Dense materials, such as brick and stone, absorb heat during the daytime and release it at night. I threaded strings of miniature lights between pots, on top of the brick patio. Broken light bulbs cause part or all of the string to fail, so be careful with them. Pots of greens and herbs placed close to the edge of the frame allowed easy access.

Herbs grew all winter in this cool but frost-free environment. Parsley, oregano, sweet marjoram, rosemary, thyme, chives, sage, French tarragon, and bronze fennel are a few of the herbs I grew in the frame. Cold frames are great for half-hardy species and those that normally stay dormant in winter. Italian oregano, tarragon, and chives, for example, retained their foliage instead of going fully dormant.

I added an adapter to the porch light socket near the patio door, and the lights’ extension cords plugged into that. With a simple flip of the switch from the cozy kitchen, the lights turned on or off. That’s one advantage of building your frames close to the house.

Remember to vent the frame on sunny days, turning lights on or off as necessary. Close it up by mid- to late afternoon.

Water as necessary, keeping the soil damp, but not wet. During mild periods of the season, add a dilute dose of fertilizer to those plants (mostly the greens) that are growing.

Power Outages

Have a contingency plan during power failures if you’re going to keep tender plants in your cold frame. Use old blankets (keep them dry), more layers of plastic, and gallon jugs filled with hot water. When this happened a few times in MD, I heated water on the wood stove for those hot water bottles and brought the most tender plants indoors.

Snow or straw piled up around the sides and a layer on top holds in a substantial amount of heat. Clear the top in the morning to allow sun to reach the plants. But if the weather is especially harsh and overcast, the plants won’t mind staying covered for a day or two.

The Maryland Greenhouse

The small greenhouse in Maryland.

I built this greenhouse from a kit purchased from a horticultural supply company. It was fairly easy to put together, although some of the pre-drilled holes didn’t quite match up and the instructions weren’t great. But the twinwall polycarbonate and sturdy framing were able to withstand considerable weight from ice and snow. The structure was attached to a foundation, which was optional but recommended.

This is where I kept more flats of tender succulents. Placed on 2 x 2″ x 8′ posts propped up on cinder blocks near the ends, the flats were heated from below with strings of miniature lights. They had the additional protection of 1 or 2 layers of clear plastic secured on the sides and suspended a few inches over the plants. When nighttime temperatures plummeted to single digits, I added a couple of old bedsheets and another layer of plastic, and then removed them once the sun hit the greenhouse. None of the plants froze.

A second heavy duty indoor/outdoor extension cord reached the porch light adapter near the cold frame, so I could turn all the lights (in the cold frame and in the greenhouse) on or off from indoors.

Double Bubble

This extra “bubble” of lightly warmed air made it possible for frost intolerant plants to survive our zone 6b winter. A bubble inside a tightly sealed unheated greenhouse (or other structure) feels up to 2 or 3 zones (up to 20-30°F) warmer at night than outside air, and even warmer with miniature lights. Keep in mind, though, that each layer reduces the amount of light reaching the plants.

Two or three rows of tender plants—all under a single bubble—occupied the center of the greenhouse. Near the perimeter sat frost tolerant cool season greens in large black nursery pots. Dark colors absorb the sun’s energy, keeping soil unfrozen for longer periods of time. Large pots work better than small pots because they store more warmth. Sometimes I stored bales of potting soil, wrapped in black plastic, on the north edge, where the winter sun would not be blocked.

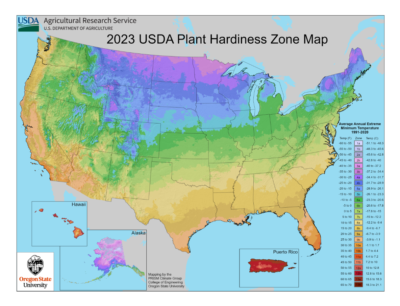

States in the middle and northern parts of the U.S., in USDA zones 4-6, benefit greatly from an extra barrier of protection from frigid temperatures. Cold hardy plants are more likely to survive than tender species in spaces with no supplemental heat.

Here in North Carolina

Since moving to Charlotte, North Carolina (USDA zone 7b/8a) in 2013, I’ve used clear plastic and miniature lights to ripen up the last of the summer vegetables. And they keep cool season greens and vegetables growing through the worst of our winter weather. To avoid any surprises, check the weather forecast daily.

Since moving to Charlotte, North Carolina (USDA zone 7b/8a) in 2013, I’ve used clear plastic and miniature lights to ripen up the last of the summer vegetables. And they keep cool season greens and vegetables growing through the worst of our winter weather. To avoid any surprises, check the weather forecast daily.

Succulents that moved with me from Maryland spend the winters in lighted cold frames after filling the sunny windows indoors (photo, right). Delicate species stay inside.

One year, an HVAC contractor came to check the heat pump, located near the lower patio. There were several flats of plants in a second cold frame down there, with miniature lights. That frame was not easily visible from the house. A couple of days later I discovered that the contractor had inadvertently disconnected the extension cord feeding power to those lights…and life to the plants! You know the rest of that story.

(***Update***: I just finished enclosing the sunny front porch at my new home in northern North Carolina, where I moved in October, 2021. This is where the succulents and other plants will spend the winter, aided by miniature Christmas lights. December, 2022)

Cautions

Cold frame covered with clear plastic and weighed down.

Make sure the miniature lights are rated for indoor/outdoor use, and that extension cords are also safe to use outdoors. I’ve been warming up the cold frames and garden plants like this for decades without mishap, except as noted above.

The tender succulents and bowls of mixed greens and herbs covered during the winter survived without damage. On nights that fell below 15°F, the temperature in the cold frame stayed in the high 30’s or 40’s, depending on the number of lights used.

Plants survived single-digit temperatures, helped by the old quilts and extra plastic placed over the frame at night. When needed, I added another string of lights. Placing the frame cover fairly close to the tops of the plants limited the volume of air those lights needed to heat. Not too close, though, or the foliage will feel the cold.

This works like a charm, but only if there’s a power source nearby. Be careful; don’t use extension cords that can’t carry the demand for power. Don’t hook up more than 2 or 3 light strings together.

There are few products on the market that demonstrate the phenomenon of planned obsolescence as clearly as cheap imported miniature lights. Stock up on them when they’re plentiful. They don’t last more than a couple of years with frequent use, and they’re becoming increasingly scarce in favor of LED’s. Tread carefully!

There are few products on the market that demonstrate the phenomenon of planned obsolescence as clearly as cheap imported miniature lights. Stock up on them when they’re plentiful. They don’t last more than a couple of years with frequent use, and they’re becoming increasingly scarce in favor of LED’s. Tread carefully!

Lastly, instructions on the packaging recommend washing hands thoroughly after handling strings of lights. There might be some lead in the wire covering.

Miniature Lights Preferred

Mini lights warm up 2 large pots of young tomatoes.

There are other types of incandescents available but watch the wattage! If bulbs are hot to the touch, the plants will think so, too, so don’t place them close to the plants. The preferred miniature lights are barely warm, so they distribute the heat evenly and gently.

Make sure the bulbs are not in contact with the plastic covering or the leaves. Avoid letting the plastic cover touch the leaves; cold transfers through the plastic and will damage foliage.

It’s best to lay the strings on the ground, around—but not touching—the stem. The warmth will rise. For potted plants, wind some of the lights around the pots. Tall plants might require lights up into their branches.

If you’re not really trying to push the envelope, the plastic bag or old sheets probably will do the trick. It’s when that sudden blast of uncommonly cold weather comes around that prompts us to take extra measures.

(***Update***: In the photograph above, mini lights kept the young potted tomatoes [in 20″ pots] and a few other plants 15° warmer on an unusually cold spring night. I placed the miniature lights on the soil surface and wound them around the pots to keep the roots a bit warmer. Plastic was closed and secured with clips. April, 2019)

Out of Reach

Where lights are impractical, there is a solution. Use large plastic mulch or trash bags, and tuck in a hot water bottle. Seriously! A repurposed gallon milk jug filled with very hot water slowly gives off heat through the night. A little experimentation will tell you if the heat is given up too quickly (wrap the jug in an old towel to slow heat loss) or insufficiently (use 2 milk jugs or larger containers). Don’t place the hot water close to the foliage. Keep this in mind when the power goes out.

Those “water wall” products you see at garden centers work on the same principle. Water that heats up in the sunlight slowly gives up that heat to the plant at night.

Plastic bags that are nested, or layered, give better protection than a single layer. Spread the opening over a wide footprint (soil’s square footage) to capture heat rising from the ground. Or simply secure a large plastic sheet to a tall stake in the ground. Weigh down the covering with rocks or bricks to keep it in place and to seal out the cold. Remove the cover in the morning.

* * * * * * * * *

I hope this information gets your garden successfully through the “shoulder” seasons, when temperatures can fluctuate wildly. Just a few readily available and inexpensive materials can prevent a total loss.

Later in the year, when autumn temperatures tumble, having materials ready for duty will extend the season. Rolls of 4-mil clear plastic—actually somewhat translucent—can be found in the hardware store’s paint department. This product (4- or 6-mil plastic) is less expensive than greenhouse film. If, however, you opt for permanent structures, the longer lasting film will be worth the investment.

If you’ve never grown cool season vegetables, these methods will open up a new world of growing opportunities. You can extend the season before and after the summer crops or protect tender ornamentals through the winter. No need to retire the trowel with the first fall frost!

Young broccoli ‘Arcadia’ in 20″ pot, where a tomato grew in the summer. Sharp-tipped pinecones discourage squirrels.

Return to the top

Since moving to Charlotte, North Carolina (USDA zone 7b/8a) in 2013, I’ve used clear plastic and miniature lights to ripen up the last of the summer vegetables. And they keep cool season greens and vegetables growing through the worst of our winter weather. To avoid any surprises, check the weather forecast daily.

Since moving to Charlotte, North Carolina (USDA zone 7b/8a) in 2013, I’ve used clear plastic and miniature lights to ripen up the last of the summer vegetables. And they keep cool season greens and vegetables growing through the worst of our winter weather. To avoid any surprises, check the weather forecast daily.

There are few products on the market that demonstrate the phenomenon of planned obsolescence as clearly as cheap imported miniature lights. Stock up on them when they’re plentiful. They don’t last more than a couple of years with frequent use, and they’re becoming increasingly scarce in favor of LED’s. Tread carefully!

There are few products on the market that demonstrate the phenomenon of planned obsolescence as clearly as cheap imported miniature lights. Stock up on them when they’re plentiful. They don’t last more than a couple of years with frequent use, and they’re becoming increasingly scarce in favor of LED’s. Tread carefully!