National Pollinator Week: June 22-28, 2020

Lavender and honey bees.

In 2007, the U.S. Senate passed a bill designating one week in June as National Pollinator Week. This legislation recognizes the importance of pollinators, including bees and butterflies, in our food supply and in the health of all ecosystems.

Every third bite of food we consume is directly attributable to pollinators. The global economic value is worth between $300 billion and $600 billion per year. Around 85% of all flowering plants are pollinated by insects, ensuring the regeneration of forests and fields as well as high yielding edible crops.

Our morning coffee beans are primarily self-pollinated, depending on crop species. Introducing bees, however, can increase the yields and lower costs of production.

In tropical regions of South America, Africa, Indonesia, and, more recently Australia, a tiny midge is responsible for pollinating cacao trees, bringing us chocolate. Chocolate contributes, incredibly, $100 billion annually to the global economy.

In the southern hemisphere, pollinator awareness programs take place in November. The Australian Government’s Department of the Environment recognizes November 8-15 as their pollinator week for 2020. Many countries throughout the world observe this initiative, and local organizations sponsor programs to raise awareness.

An outdoor project can be an enjoyable and healthy way to use our time. Having the children participate will teach them valuable skills they will carry with them wherever they live.

And, if there’s one thing we could use more of, it’s nature.

A bee house.

What Bees and Butterflies Need

All living creatures need food and water, shelter, and a place to raise their young. By adapting the way we maintain the property around our homes, we can achieve both an attractive landscape and one that fosters populations of wild creatures. Currently, 40% of the insect pollinator species are at risk of extinction. A few of us can make a small difference in our neighborhood; millions of us can really shake it up!

Houses—entire communities—generally have been built after felling all the native trees, bulldozing the rest, and covering the ground with a high maintenance lawn. Streams were diverted to concrete pipes underground, taking habitat from frogs, salamanders, and turtles. Where this tradition is changing, developers are roping off and protecting native stands of trees and understory species.

Maybe the builder spotted in a fast growing silver maple, a row of clipped hollies along the foundation, and a couple of forsythias in the back. Well, that won’t do much for all the bees and butterflies, or for the hummingbirds, bats, moths, and beetles that pollinate our crops and wild plants. And right there, in this yard and in that yard, lie the broken links in the food chain. Our monocultured and unnaturally manicured properties are sold as low maintenance, but there’s little life there.

The Missing Elements

We concentrate instead on creating an “indoor oasis”, untroubled that the quiet stillness outside the door is not what Mother Nature had intended. No birds chirping or warbling…no cicadas or katydids…no lizards leaping for their dinner…nowhere for the dragonfly to land.

Yes, we need more nature in our lives. By cultivating a relationship with the natural world, there’s more than just a pretty sight beyond the living room windows. There’s life. Birds will continue to follow million-year-old migration paths. Mason bees and swallowtail butterflies will secure homes for their young. And there will be less talk of scarcity.

Need to feel better? Try gardening!

1. A Garden of Annuals for Bees and Butterflies

Bumble bees in the marigolds.

Maybe this week’s goal is to carve out a section of the big lawn in the sunny back yard, and plant a flower garden. Mid summer isn’t too late for annuals, either from seeds or from transplants. Or, for now, consider how your family can use the property in the future. It’s always a good time to decrease the amount of lawn space we have to mow, fertilize, and treat for insects and diseases.

Be sure to plant significant drifts of flowers instead of a dot of zinnias here and a couple of marigolds over there. Large blocks of similar colors are more likely to get attention from pollinators. If your space is limited, though, there are some options. Sunny windowbox gardens and pots filled with bright colorful flowers will generate interest from the pollinators. Or perhaps there’s room for hanging baskets.

Each pollinator has its own preferences. Hummingbirds are attracted to the color red, but bees can’t see it. Bees are initially attracted to blue, yellow, and white, and then will visit a red flower nearby. Hummingbirds can feed from long tubular flowers, but hover flies need short little flowers.

At night, moths can detect white or pale colored sweet-smelling flowers that are open at that time. Almond flowers are pollinated primarily by honey bees, and tomatoes by bumble bees. Butterflies are especially interested in landing platforms, such as those found on plants with wide, flat flowers.

What Is An Annual?

An annual grows from a seed that germinates, generally, in spring or summer. It grows for several weeks to a few months, matures, and then begins to flower. Many species of annuals bloom all summer, until frost ends their lives in autumn, roots and all. But, by then, the plant will have set seed, with help from the local pollinators. An annual completes its life cycle within one growing season.

Those seeds will remain dormant over the winter, protected by their seed coats. With favorable weather conditions next spring, some of the seeds will germinate. Many, however, will be consumed by small mammals, birds, and insects.

What Do Pollinators Do?

Bumble bees on passion flower vine. Arrangement of flower parts facilitates pollination.

Bees and butterflies, and other pollinators, transfer pollen grains from the male anthers of a flower to the stigma, the female part of a flower. Sometimes male and female flowers grow in separate flowers on the same plant (that’s a monoecious plant). And other plants have either all male or all female flowers (dioecious plants). Some have both male and female reproductive elements within each flower (perfect flowers).

Pollinators don’t do this intentionally. Instead, their goal is to collect the flowers’ pollen and nectar. They inadvertently pick up the pollen on their hairs or wings, after being lured in by the flowers and the sweet nectar. Then the pollinators transfer pollen from flower to flower, from plant to plant, as they forage. Thus, they enable fertilization of the ovules, germ cells in the ovary of the female flower.

The male and the female parents must be the same species in order for their chromosomes to be compatible. However, interspecific and intergeneric hybrids sometimes do occur among closely related individuals.

The end result is a ripe fruit with viable seeds. That could be a zinnia’s seedpod, for example, or a blueberry, a peach, or a tulip poplar’s samara.

Cross Pollination

Ah, the genius of nature. Pollen grains and stigmas in many species mature at different times, preventing self-pollination.

Moving pollen among different plants of the same species permits cross-pollination, resulting in stronger genetics and, potentially, a better future for the species. Apple trees and blueberries are two crops that benefit from cross-pollination.

Single? Double? Triple?

Catharanthus ‘Soiree Double Pink’, an annual vinca. Extra petals replace reproductive parts.

Flowers with single rows of petals usually have more pollen and nectaries than those with a more complicated petal structure. Plant breeders all over the world have brought to market thousands of these kinds of fluffy triple-flowered hybrids, and they are beautiful. That’s fine, for aesthetics.

But, for bees and butterflies, there’s less treasure for them in flowers filled with petals. Reproductive structures that produce nectar and pollen are often reduced and replaced with additional petals (photo, above). Collecting pollen or nectar from these packed doubles is less efficient, and requires extra visits to gather sufficient quantities. So, pollinators will look for more desirable plants elsewhere, to conserve energy, and avoid such anomalies of nature.

When choosing the varieties for your annual garden, keep these details in mind. Gardens loaded with heavy producers of nectar and pollen (in other words, single flowers) will better serve the pollinators that visit them.

Sunflowers

Many varieties of recent sunflower introductions have been hybridized to grow flowers with very little or no viable pollen at all. When looking through catalogs, make note of the ones called “pollenless”. These varieties will make less of a mess on the credenza and won’t cause you to sneeze. But they have little to offer bees and butterflies.

Many varieties of recent sunflower introductions have been hybridized to grow flowers with very little or no viable pollen at all. When looking through catalogs, make note of the ones called “pollenless”. These varieties will make less of a mess on the credenza and won’t cause you to sneeze. But they have little to offer bees and butterflies.

Pollenless sunflowers won’t develop mature seeds filled with sustenance for birds and other animals. If pollinators and full seedpods are what you want, ask the seed supplier for varieties that make edible seeds, not just edible flowers.

These varieties of sunflowers will attract pollinators and make edible seeds: ‘Big Smile’, ‘Black Peredovik’, ‘Chocolate’, ‘Giganteus’, ‘Hopi Black Dye’, and ‘Kong Hybrid’. Also, ‘Mammoth Grey Stripe’, ‘Mammoth Russian’, ‘Paul Bunyan’, ‘Royal’, ‘Royal Hybrid 1121’, ‘Sunzilla’, ‘Super Snack’, and ‘Titan’.

Sunflowers have a row of showy ray florets surrounding the disc florets. Disc florets open slowly over time, from the outer edge to the center, ensuring many visits from different pollinators.

The Asteraceae family is perhaps the largest, with 1900 genera and over 32,000 species. (The orchid family is its main rival, but no one knows exactly how many species are in either family.) Members of this extended family include sunflowers, dianthus, lettuce, coreopsis, marigold, zinnia, coneflower, gerbera daisy, chrysanthemum, and shasta daisy.

Where to Plant?

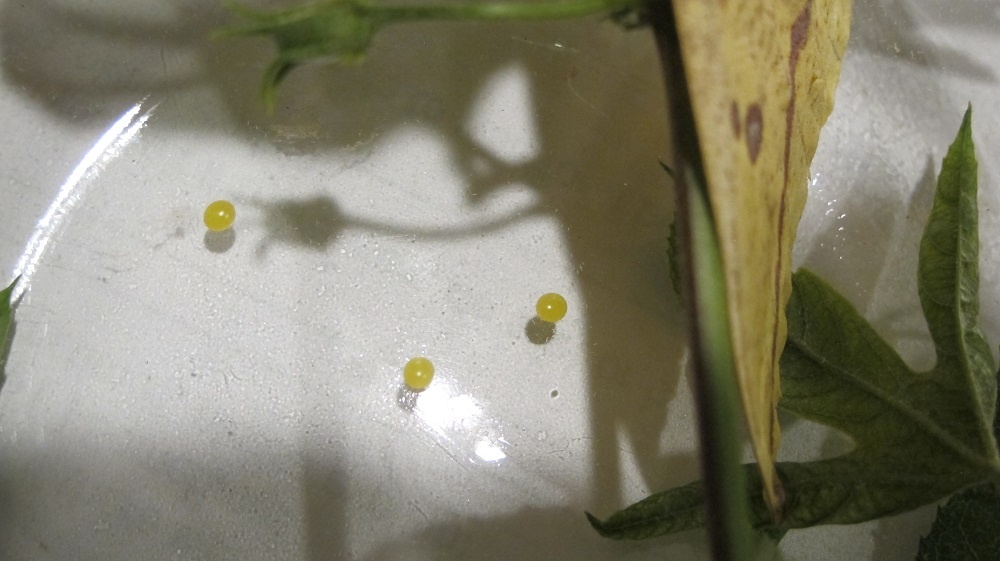

Thin peduncle (flower stalk) under summer squash flower indicates a male flower. A female flower has a rounded peduncle.

A large bed of color around the patio or the mailbox, a free-standing raised bed, and a border close to the vegetable garden are just some of the possibilities. Farmers often include wide bands of wildflowers alongside their fields of crops for better pollination and heavier yields.

One plant that attracts all sorts of pollinators is ‘African blue’ basil. This is a sterile herb—unable to set seed—so it flowers constantly. Other varieties of sweet or flavored basils customarily are used in the kitchen. Plant an ‘African blue’ basil in early summer, close to tomatoes, peppers, and squash to encourage bees to visit the veggies. And let it flower.

Check with local garden centers to see what they have available. Ask for help choosing annuals—seeds or transplants—that attract pollinators.

Before you do any digging, ask your municipality (call 8-1-1) to mark underground utilities. Whether you’ll be tilling the area or digging it by hand, you’ll certainly want to avoid damaging any of those lines.

Locate the garden where a source of water is easily accessible. New transplants and young seedlings will need consistent moisture until they’re established. During summer drought, water the bed thoroughly every week or so.

Sun or Shade?

Fuchsia flowers.

Find an area that gets full sun if you want lots of flowers. Full sun is at least 6 hours, but annuals will positively thrive in more sun than that. Summer annuals blooming heavily in sun will attract the most pollinators.

But several species prefer shade, such as impatiens. The ‘Imara’ impatiens, resistant to impatiens downy mildew, provides a carpet of color under the trees and shrubs. This plant attracts bees and butterflies, and also hummingbirds.

Where summers aren’t too hot, the fuchsia baskets (photo, above) will entice the hummingbirds to visit every day, like clockwork. This plant does well in dappled shade or early morning sun. And it likes moist soil. As the temperatures climb and fuchsia fails, hummingbirds will flock to the single petunias and salvias, which need lots of sun. They also visit herbs in bloom, including basil and lavender.

How Big Is Big?

Hummingbird.

With proper soil preparation and regular maintenance, a plot that measures 10′ x 6′ can become a magnet for pollinating insects. The flowers will buzz with activity from perhaps dozens of species of bees and butterflies, and moths and hummingbirds, too.

This country is home to over 4,000 species of bees alone! More than 20,000 species live around the globe. Some live in colonies, and many are solitary creatures. Interestingly, the honey bee is not native to the United States. It was brought by European settlers hundreds of years ago and proliferated throughout the country.

To increase the activity and the number of pollinating species lured in, make the bed even larger. And include more variety in the plants selected. Use masses of the same plant, and repeat elsewhere in the garden, if you want. Planting larger blocks of a particular color or flower type will attract more pollinators than scattering them about.

If this is your first gardening effort, keep the garden a manageable size so you’re not overwhelmed. There will be maintenance involved! Weeds, no doubt, will have to be pulled. And your garden will need fertilizer a few times through the growing season for the best results. An inch or two of mulch will help cool the soil, retain moisture, and restrain weeds. You can always expand the area as you gain confidence in your skills.

Container Gardens

Even in a very limited space, some of the local bees and butterflies will find the lovely combination pots on your balcony or the patio. Use bright colors, and have your camera ready—for the flowers and their visitors. Once they find their preferred flowers, pollinators will come back day after day.

Remove seedpods to encourage more flowers to develop, although finches and other birds will feed on seeds remaining on stalks late in the season. Fertilize regularly to keep the plants in prime condition. Plants in containers might need daily watering.

Added Benefits

Blueberry flowers.

Insects are on a constant lookout for sources of pollen and nectar. You might discover your fruit trees, blueberries, and vegetable crops yielding heavier harvests since installing a flower garden.

Edible crops and plants growing naturally in or around your property will benefit from complete pollination because of the larger populations of pollinators. Include plants whose flowers attract pollinators early and late in the growing season, as well as during the summer months.

-

-

Bumble bee visiting broccoli flowers.

-

-

Flowers on mustard greens. This edible plant readily self-seeds.

-

-

Red Russian kale in bud.

I grow many kinds of greens (photos, above) in the cool seasons. Before they’re replaced with summer crops, I allow them to go to flower in late winter to early spring. Most are biennials in the Brassicaceae family, including kale, collards, broccoli, arugula, and mustard greens. Although they don’t require pollination for a harvest, the cruciferous flowers provide pollen and nectar for bees, braconid wasps, hover flies, and other pollinators at the time of year when little else is available.

Pansies and violas provide sustenance for bees that emerge on pleasant winter days. These colorful cold-tolerant biennials grow in garden beds and in containers.

Braconid wasp.

The tiny non-stinging braconid wasps are hardly noticeable, but they help keep populations of live-bearing aphids in check. A female braconid wasp deposits an egg in or on an aphid. After hatching, the wasp larva consumes the tissues, killing the aphid. One braconid wasp can parasitize 200 aphids in her brief lifetime. Adults emerge to mate, and a new generation of females will begin hunting aphids.

Pollen is an important food source for the braconid wasps, which will feed on some aphids as well. So, even these tiny insects help pollinate plants.

Photo at right shows a wasp about to deposit some eggs. White aphids have been parasitized, and the others are alive. I’ve often seen leaves with a hundred aphid mummies (the aphid’s empty exoskeleton) attached, with no living aphids.

Planting a wide variety of flowers helps these beneficial insects. Self sustaining populations of beneficials contribute to the overall health of your garden, reducing or eliminating the need for pesticides.

Let’s not forget about the birds! Although most species, other than hummingbirds, don’t play a major role in pollinating plants, songbirds certainly have a place in any natural ecosystem. We can play an important part, in our own yards, by maintaining an environment that fosters healthy populations of native animals.

The tiny ruby-crowned kinglet at a winter feeder.

The numbers of many species of birds are declining, due primarily to human interference. We’ve removed their habitat in favor of expansive lawns and non-native trees and shrubs. And we’ve killed off their food sources by spraying pesticides every time a “bug” shows up. Can we please adopt a new attitude?

After all, birds help by consuming huge numbers of insect pests that otherwise could destroy crops or damage potted plants. Birds and bats keep mosquitoes and moths in check. More insects in the garden will support more avian activity.

Restoring healthy populations of all native animals and insects will return balance to the ecosystem. Sometimes, though, the songbirds fall prey to foxes, snakes, or hawks. Predator and prey: yes, folks, that’s how it works.

There are many benefits to living in modern society, but loss of habitat for wild creatures is not one of them. Letting nature be is a crucial step in re-establishing native populations and preventing extinctions.

Let ‘Em Seed About

Finches, sparrows, and chickadees feast on seeds that develop after the flowers fade. So, don’t be too hasty to deadhead the last round of flowers. Allow them to remain in place through the fall and winter, so the birds have another food source available when they need it. Birds will soon recognize your property as a wellspring of year-round sustenance.

Bright yellow and black American goldfinches are fond of zinnias, cosmos, salvias, and asters that have gone to seed. In late summer and autumn, the finches, northern cardinals, thrashers, blue jays, and other animals eagerly consume seeds atop the black-eyed Susans and tall sunflowers. And you might notice plants germinating next spring from seeds the birds overlooked.

Water

Include a source of clean water for the birds. A birdbath in the garden is fine, or you could keep a large plant saucer on the deck. Change the water frequently to prevent mosquito wrigglers from reaching adulthood.

The bees and butterflies also will appreciate a small saucer of water on a hot summer day. Place a flat rock island in the water for safe sipping. A mud puddle, just a bare patch of wet sandy clay, provides moisture and minerals for butterflies.

Another benefit of growing a garden of annuals is the almost endless supply of cut flowers for indoor arrangements. Include plans to expand the garden next year, to keep the pollinators happy, too. Check with your agricultural extension service to see which flowers last longest in a vase.

Try Some Of These For the Bees and Butterflies

Ageratum, alyssum, bachelor’s button, cleome, cosmos, fuchsia (hummingbirds), herbs, impatiens, lantana, marigold, and pentas. Rudbeckia (annual and perennial varieties of black-eyed Susan), salvia (annual and perennial types, a hummingbird favorite), some of the sunflowers, tithonia, verbena, and zinnia.

-

-

Sweet alyssum.

-

-

Cosmos.

-

-

Zinnia angustifolia ‘Star’ series, disease resistant.

Headings

Page 1: National Pollinator Week, June 22-28, 2020, What Pollinators Need (The Missing Elements), and A Garden of Annuals for Bees and Butterflies (What Is An Annual?, What Do Pollinators Do?, Cross Pollination, Single-Double-Triple?, Sunflowers, Where To Plant?, Sun or Shade?, How Big Is Big?, Added Benefits, Vegetables and Fruits, Braconid Wasps, For the Birds, Cut Flowers)

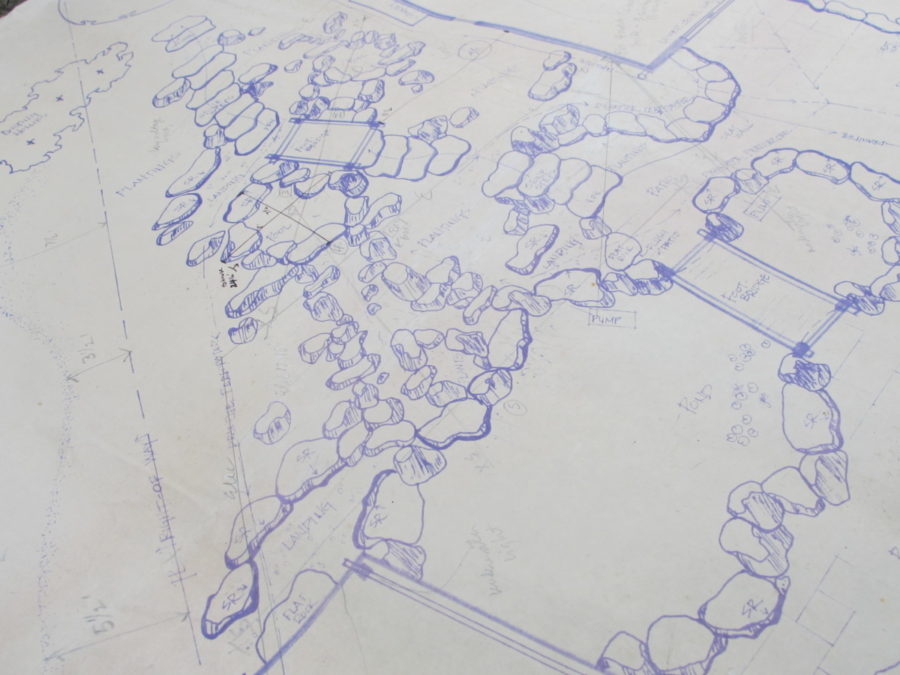

Page 2: Perennial Favorites For Bees and Butterflies, Lavender, Herbs, Brush Piles, Go Native, A Comprehensive Garden Plan (Dream, Plan, and Implement, On the Right Path, Stone, Diversify, Some Native Woody Plants, Asking for Help, Dig In!, Small Is Beautiful), and Links

Return to the top

The hollies (Ilex spp.) are another genus of primarily dioecious (Latin for “two houses”) plants that fruit on female plants. They ordinarily require a male plant, or pollenizer, to set fruit, although holly pollenizers (the males) themselves do not set fruit. Modern breeding techniques have yielded several cultivars that can make berries without pollination.

The hollies (Ilex spp.) are another genus of primarily dioecious (Latin for “two houses”) plants that fruit on female plants. They ordinarily require a male plant, or pollenizer, to set fruit, although holly pollenizers (the males) themselves do not set fruit. Modern breeding techniques have yielded several cultivars that can make berries without pollination.

Many varieties of recent sunflower introductions have been hybridized to grow flowers with very little or no viable pollen at all. When looking through catalogs, make note of the ones called “pollenless”. These varieties will make less of a mess on the credenza and won’t cause you to sneeze. But they have little to offer bees and butterflies.

Many varieties of recent sunflower introductions have been hybridized to grow flowers with very little or no viable pollen at all. When looking through catalogs, make note of the ones called “pollenless”. These varieties will make less of a mess on the credenza and won’t cause you to sneeze. But they have little to offer bees and butterflies.

A paved pathway takes visitors through a succession of gardens. There’s an herb garden, a fragrance garden, and one that highlights tropicals. And a miniature train garden, succulents, and roses. Annuals are planted here and there, providing vibrant color and nectar for the

A paved pathway takes visitors through a succession of gardens. There’s an herb garden, a fragrance garden, and one that highlights tropicals. And a miniature train garden, succulents, and roses. Annuals are planted here and there, providing vibrant color and nectar for the

And for good reason: we rely on pollinators for more than a third of our entire food supply! Without the bees, butterflies, bats, and hummingbirds, we would not be able to feed our growing populations. Apple, peach, and nut trees, tomatoes and peppers. Zucchini, cucumbers, berry bushes, and farm animal feed. These are just a few crops that depend on these little critters. Trees, grasses, shrubs, and wildflowers also rely on pollinators for procreation.

And for good reason: we rely on pollinators for more than a third of our entire food supply! Without the bees, butterflies, bats, and hummingbirds, we would not be able to feed our growing populations. Apple, peach, and nut trees, tomatoes and peppers. Zucchini, cucumbers, berry bushes, and farm animal feed. These are just a few crops that depend on these little critters. Trees, grasses, shrubs, and wildflowers also rely on pollinators for procreation.