Page 4

Tips For Watering Herb Gardens

Watering plants is part science and part instinct. Experience will guide you as you observe how plants react to your watering practices.

Generally, water pots thoroughly. Saucers catch some of the excess, and are optional, of course, but empty them after 10 or 20 minutes. Use non-porous saucers (plastic, glazed) on surfaces that could be damaged by moisture.

During rainy periods, herbs could suffer from overwatering if their pots sit in soupy saucers all the time. Remove them or place them upside-down under the pots. When dry weather returns, replace the saucers.

Reservoirs under Earth boxes or large plastic pots might hold too much water for herbs or for any young plants. Tip the containers to empty excess water if the soil is moist enough.

Herbs with soft, leafy growth (such as basil, mint, arugula, Par-cel, parsley, and cilantro) should be kept moist to slightly moist (not wet) at all times. The woody herbs, such as lavender, rosemary, sage, thyme, and bay, can go somewhat dryer. During periods of frequent rain, I usually place the water-sensitive plants under an overhang where they get light but not rain. Herbs don’t need to be misted.

Transpiration

Transpiration is the natural flow of water through the plant’s vascular system. Water moves from the soil…into the roots…through the stems…to the leaves…and out the stomates (pores) to the atmosphere. Water moving through the plant’s system of xylem tubes, without interruption, prevents the plant from wilting. It keeps the leaves turgid.

Moving air, dry air, sun, and warmth around the foliage exert “transpirational pull” on this column of moisture. Gravity and other properties of water, including cohesion (water molecules sticking to each other) and adhesion (water molecules sticking to other surfaces), also influence water movement through a plant’s vascular system.

Why Plants Wilt

Most often, wilting leaves indicate that the soil is either too dry or too wet. Wilted plants kept too dry will recover when watered, if they don’t stay dry for too long (photo, above). Plants also wilt from overfertilization, strong wind, root rot, disease, abrupt changes in temperature, and chemical damage.

Most plants die if the soil has been too wet for a period of time, having been deprived of oxygen. Lack of oxygen interferes with the roots’ ability to respire, and, therefore, with their growth. Respiration is the process of utilizing oxygen and the sugars made from photosynthesis, and turning it into carbon dioxide, water, and the energy needed to fuel cell function and growth.

Pathogens, such as bacteria and fungi, multiply in wet soil and exacerbate the distress. When roots die, they can’t replace the water lost from the foliage to the atmosphere. So, what happens next? Right—the plant wilts!

The Mediterranean herbs (thyme, lavender, oregano, sage, rosemary) are particularly sensitive to prolonged periods of saturated soil. If these herbs are badly wilted from overwatering, harvest the foliage and dry it to get something out of the plants. Cut back the stems and wait a few weeks to see if new growth emerges.

Place a wet pot of soil on a terry cloth towel to absorb excess water. Or take it out of the pot to accelerate drying. Downsizing the pots—or adopting different watering techniques—might help prevent this problem in the future.

Testing for Moisture

It’s impossible to say how many days should elapse before watering again. So, how do you know what to do?

- Your finger is the best indicator of soil condition, so feel the soil 1″ to 2″ into the pot. Check in a few places around the medium. Although the surface is dry, the soil 1″ below the surface can still feel moist. In this case, the plant doesn’t need water yet.

- You can also use a thin unfinished wooden dowel to test for moisture. Plunge it all the way to the bottom of the pot, leaving it there for 15 minutes. Remove it and wipe off the particles. The wood darkens in moist soil.

- Periodically lift your potted plants and feel the weight. You’ll begin to notice how heavy a moist pot feels, and how light a dry pot feels.

- One way to distinguish a wet clay pot from a dry one is by tapping or flicking the side or the rim of the pot. With a moist medium, you’ll hear a dull thud. A dry pot has a hollow, higher pitched sound.

- Some gardeners rely on moisture meters, but I’ve never found them to be very accurate. The higher priced instruments probably are more reliable.

From Season To Season

Potted herb gardens outside dry fast in warm sunny weather. Herbs in small pots or in dense combinations might need daily watering. When autumn chill comes around, or during overcast weather, you won’t need to water very often, and the rain might provide enough.

The summer sun’s intensity drives robust photosynthesis, resulting in vigorous growth. Plants growing indoors, however, receive fewer hours of sunlight, so all processes slow down: less photosynthesis, reduced transpiration, slower growth. Decreased light causes internodes (the stem segments between leaf attachments) to stretch. That weak “growth” can be corrected by providing more sunlight or artificial light. Lower temperatures might also help prevent stretch.

Herbs growing in small to medium size pots are more adaptable to indoor life. So, plants in very large pots probably will benefit from being separated into individual pots or into containers holding just 2 or 3 herbs. Large herb gardens placed in a sunny conservatory, though, need not be altered.

Water Temperature

Basil is the most temperamental herb when it comes to soil temperature. It enjoys lukewarm water, around 85°F, during the cooler months, indoors, or when starting seeds. Lemongrass and stevia also like lightly warmed water.

Chervil, cilantro, and French tarragon like cool water.

Always check the water coming out of the hose in the garden. If the hose has been sitting in the summer sun, the first 1 or 2 gallons of water could be too hot for any plants.

Fertilizing Herb Gardens

All plants growing in containers will need fertilizer at some point. Since their roots are confined to pots, they can’t search through the soil for a new supply. Lack of nutrients, particularly nitrogen (N), is a limiting factor where growth is concerned. This macronutrient is critical to the formation of chlorophyll, the green pigment contained in chloroplasts inside the cells.

Chlorophyll enables photosynthesis, the process by which energy received from the sun, in the presence of oxygen and hydrogen (from water) and carbon (from carbon dioxide), transforms these elements into sugars. Plants can feed themselves, but we have to provide the necessary ingredients.

Macronutrients and Micronutrients

Macro

Approximately 96% of a plant is composed of just 3 elements: carbon (C), oxygen (O), and hydrogen (H).

Of the nutrients we supply, nitrogen (N) is the element needed in largest quantities. As nitrogen levels drop, the plant enters the stage called “hidden hunger”. The plant might look okay, but it’s beginning to translocate nitrogen from the older part of the plant to the growing tip, sacrificing older leaves. Lower leaves will turn yellow and might fall off, and the color of the plant, overall, will pale. New growth slows considerably, and leaves grow thin and weak. Nitrogen is highly mobile and quickly leached from the soil.

Two other primary macronutrients are phosphorus (P) and potassium (K). N-P-K always appear on a fertilizer’s label in that order. Plants also require the secondary macronutrients, sulfur (S), magnesium (Mg), and calcium (Ca).

Micro

Equally important but needed in tiny amounts are the micronutrients (boron, chlorine, copper, iron, manganese, molybdenum, and zinc). A few other elements (cobalt, nickel, sodium, vanadium) are needed by certain groups of plants, and silicon is becoming increasingly more commonplace in potting soils.

All these nutrients allow plants to perform thousands of chemical processes to fuel their photosynthetic, respiratory, growth, and reproductive functions.

It’s better to maintain nutrient levels that prevent deficits rather than trying to reverse symptoms of undernourishment.

Organic or Synthetic?

Organic matter—material composed of once-living organisms—contains nutrients required by herbs. Organic fertilizers include fish emulsion, earthworm castings, compost, ocean-and-farm products, bat guano, composted manure, and many others. These products also feed the microscopic organisms living in the soil. Microbes break down organic matter into simpler nutrients plants can absorb, receiving carbohydrates and proteins in return.

Organic matter is not the same as a certified organic product. Fertilizer and soil manufacturers can apply to the U.S. Department of Agriculture for “certified organic” status. Once approved, they may print the OMRI (Organic Materials Review Institute) logo on their labels. Certified organic growers use mostly OMRI products in order to retain their certified organic designation.

Where Synthetics Might Be Better

Although I prefer using organic fertilizers, there are certain applications where synthetic products work better. One is in cold weather. Microbes are dormant when the soil cools, so they can’t break down the organics. Mustard greens, kale, parsley, broccoli, collards, green onions, spinach, and other cool season crops need fertilizer—even in winter. So, that’s when I use soluble fertilizers, which keep the plants growing and producing as long as temperatures don’t plummet.

Another case where synthetics are recommended is when a plant needs a quick injection of nutrients to get the plant back to health. Nutrients dissolve in water, and soluble salts enter the plant’s system faster than waiting for organics to break down. But, for the overall health of plants, soil, and the environment, organic nutrient sources are more appropriate.

How Often To Fertilize Herb Gardens

Attentive gardeners provide nutrients before plants show signs of distress. Plants growing in well-prepared garden soil might be able to get through a growing season without additional nutrients, but that’s not feasible in potted herb gardens.

Fertilizers with low numbers can be used more frequently than those with more concentrated formulations, such as 20-20-20. Many of the organic products measure in the single digits, for example, 2-4-1 or 5-1-1. Crowded pots, small pots, and leafy plants (basil, arugula, cilantro, parsley, Par-cel, mint) require more fertilizer, perhaps every 2 weeks. I fertilize large pots every 2 to 3 weeks (depending on the herbs) in the growing season, and less often in cool weather.

This is not to say that you can’t use the stronger formulations. When I apply soluble fertilizers for edible plants, or when fertilizing in winter, I dilute them more than the label recommends. Lush growth from stronger products, however, invites trouble from insects and diseases, which favor soft, tender tissues.

Frequent rains leach some of the nutrients, particularly highly soluble nitrogen, from the soil. The only way to make up for this loss is to shelter those pots from the rain or to fertilize our plants.

When We Don’t Fertilize

It’s commonly recommended, by some, not to fertilize herbs at all. Keep in mind that underfertilized herbs lack full, deep color. If they don’t look good enough to eat, they aren’t good enough to eat! Basil, for one, tastes absolutely terrible and bitter once the color goes off. Some have written that the reason for this is letting basil go to flower, but flowers have nothing to do with the quality of the foliage.

Many are fearful of using fertilizers on herbs, afraid they will make the plants toxic. This simply is not the case. Fertilizers, whether synthetic or organic, break down in the soil to simpler compounds. The plants take in these nutrients, as simple ions, and rebuild them into molecules they need to function—in other words, plant tissue.

I’ll mention again that I prefer the organic sources of nutrients (compost, composted cow manure, fish emulsion, Neptune’s Harvest, Sea-Plus, and the Espoma brand of fertilizers), which add beneficial components (amino acids, plant hormones, mycorrhizae) to soil in addition to the nutrients.

The Taste Test

If you want to put this to the test, grow 2 identical 8″ pots of sweet basil, such as ‘Genovese’. Use the same soil for each of them, and grow them outside this summer, side by side.

For Basil #1, add only water when needed. For Basil #2, water when needed, and add fish emulsion to the water once every 2 weeks. Then let me know which one has better flavor and growth after 2 or 3 months.

Temperature For Herb Gardens

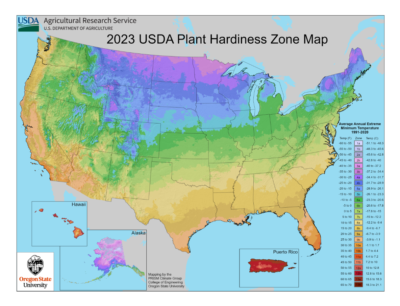

Many of the herbs we use in cooking are hardy perennials and will survive some really cold winters. Refer to the zone ratings I’ve included in the “Perennials” section and to the USDA map, above, to see which species can stay outside where you live.

Most herbs can tolerate cooler temperatures indoors in winter, even as low as the 40’s at night next to a cold window. On extremely cold nights where ice forms on the window, pull the herb garden away from the window or place a large piece of cardboard between the glass and the plants.

Basil is the most temperature-sensitive herb—the last to be placed outside in spring and the first to come indoors in autumn. Basil does not like cool weather at all! Because it’s a warm season annual, try to maintain temperatures in the high 60’s and into the 80’s. Basil will survive an occasional night in the 50’s, but it can’t tolerate repeated exposure to chill. It dies with frost but begins to decline with temperatures below 60°.

At the other end of the thermometer, parsley and cilantro love cool weather. When properly hardened off, they will live through the winter outdoors in the southern United States and partway up the coastlines. A straw or pine needle mulch will hold some warmth in the ground and help them get through the coldest months of winter. Or use a cold frame for shelter from the extremes.

As Temperatures Change

Italian oregano at the end of winter.

Over the summer, start thinking about where you’re going to keep the herb pots when temperatures drop in autumn. Perennial herbs that go dormant outdoors usually stay in leaf indoors.

Find a less exposed site outside, against the south side of the house if your winters are moderate. Or move them into sunny windows indoors for continued growth.

The severity of winter weather determines the potential for a perennial plant to keep some, all, or none of its foliage. Chives, thyme, and Italian oregano, for example, always lost all their leaves in the Maryland gardens. Here in North Carolina, though, they go semi-dormant, and usually retain some leaves through the winter (photo of oregano, above).

Rosemary never lived through a Maryland winter, and even in North Carolina, it occasionally perishes in harsh conditions (windy, wet, too cold).

Among the perennial herbs growing outside, chives is always the first to start vigorous growth, usually by late winter. And parsley offers leaves for harvesting through cold weather before going to flower. What could be better on a cold winter day than picking fresh herbs for chicken soup? I cluster them together in the warm microclimate outside the back door, so they’re not fully exposed to winter’s worst.

Headings:

Page 1: The Gift That Keeps On Giving, Choosing the Right Containers for Herb Gardens (Style and Size, Window Boxes, Long Toms, Plain Pots, Pot Color), Choosing the Right Plants for Herb Gardens (A Proper Fit, Seeds and Transplants, What’s the Difference Between Herbs and Spices?)

Page 2: Which Herbs Are Annuals? Biennials? Perennials?

Page 3: Herb Gardens Close To the Kitchen, Combination Pots, Potting Up Herb Gardens, How To Maintain Herb Gardens (Light, Natural Sunlight, Artificial Light)

Page 4: Tips For Watering Herb Gardens (Transpiration, Why Plants Wilt, Testing for Moisture, From Season To Season, Water Temperature), Fertilizing Herb Gardens (Organic or Synthetic?, Macronutrients and Micronutrients, How Often To Fertilize Herbs, When We Don’t Fertilize, The Taste Test), Temperature (As Temperatures Change)

Page 5: Common Pests (Better Options To Eradicate Pests, Bacillus Thuringiensis, Horticultural Oil, Organic Sluggo, Plain Water), Girth Control (It’s Thyme For Drying, Which Herbs Dry Well?), Renovating Herb Gardens (Propagating Herbs)